The "Falstaff Problem": Why Duolingo Adventures are almost genius

Duolingo’s activity is a step forward for language learning. But as GBL developers, we see one crucial missed opportunity: agency.

Duolingo's Big Leap

Let’s get all our cards on the table before we start – for many of us in the educational and game development world, our relationship with Duolingo is… well… complicated.

You can’t argue that it has become an undeniable force of nature that has done more for language-learning accessibility than any platform in history. At the same time, its pedagogical approach (especially for advanced learners) gets a lot of (often justified) side-eye from educators.

For years, Duolingo has been the undisputed king of gamification. Streaks, leaderboards, XP, gems… these are all extrinsic rewards applied to what are, essentially, high-tech flashcards.

But about a year ago, they released Duolingo Adventures, and our ears at Level Best perked up. This wasn’t just gamification. This was a clear, intentional step into the world of true Game-Based Learning (GBL).

And as GBL-focused developers, we loved it. It’s so, so close to being brilliant. But its one big flaw is a perfect lesson in what separates a “quiz in a costume” from an actual game or something more “game-like”.

What Adventures Gets Right

First, let’s give credit where it’s due. Adventures is a massive step up from the main path, and it nails some key GBL fundamentals.

Context is King: This is the single biggest win. You’re not just learning the abstract phrase “I need a key.” You’re in a room, you need to leave, and you’re actively looking for the llave to open the puerta. The language is now a tool to understand and navigate a world, which is exactly how we learn in real life.

Narrative Motivation: A simple story (“Help Falstaff,” “Find the hidden object”) is a much more powerful intrinsic motivator than an extrinsic XP bar. I’m proceeding because I’m curious about what happens next, not just because I want to get my +50 XP.

A “Safe Failure” Space: The feature (mostly) doesn’t penalise you with “energy” loss for selecting a funny or wrong answer. This is crucial for GBL. It encourages experimentation and exploration—two pillars of play.

Curiosity-Driven Exploration: You can click around the environment! You can tap on a gato or a silla just to see what the word is. The game is rewarding curiosity, which is a core GBL loop.

It all looks and feels like a classic point-and-click adventure game. But when you start to “play” it, you hit a wall.

The "Falstaff Problem": Where It Fails as a Game

This brings me to the “Falstaff Problem.”

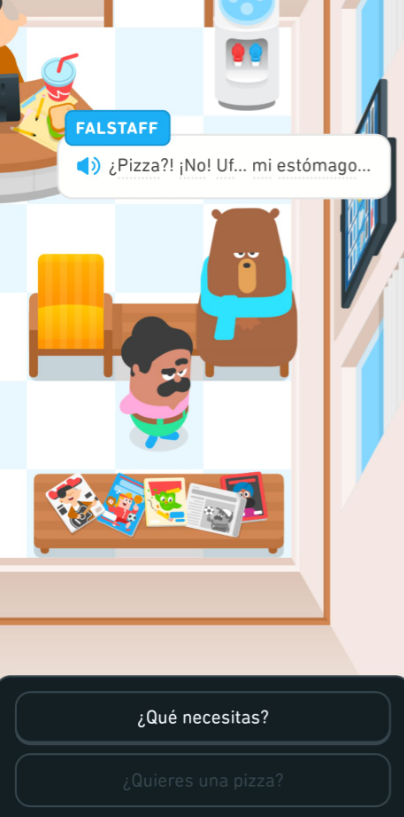

I was playing an Adventure where the character Falstaff was sick in a doctor’s surgery. The game presented me with dialogue choices. So, like any good game developer, I immediately tried to break it.

I saw the “correct” (nice, helpful) answer, and I intentionally chose the opposite—something mean, or unhelpful, that would clearly make him feel worse. I clicked it, braced for impact…

…and nothing.

Well, not nothing. I got a simple text response like, “Oh, that’s not the right thing to say,” and was prompted to pick again.

But Falstaff himself? No reaction. His character model didn’t change. He didn’t groan, turn a different color, or get angry. The game world did not react to my choice. It was just a script, waiting for me to find the “Continue” button.

This is the “Falstaff Problem,” and it’s the core illusion of agency.

The game offers what looks like a choice, but it has no impact on the game’s state. It’s a “railroad” narrative disguised as an interactive one. The game provided textual feedback (you’re wrong) but not systemic feedback (the world shows you that you were wrong).

This is why it’s not a GBL experience… yet. The goal instantly reverts from “use language to help Falstaff” to “guess the correct text string to make the ‘Next’ button appear.”

How We'd "Level Up" Adventures

If our studio were prototyping a fix, we wouldn’t suggest a grand project to change this. The “Falstaff Problem” can be solved with much simpler, more powerful mechanics.

1. The “Simple State” Fix (Fixing Falstaff)

The Mechanic: Create simple, swappable character sprites.

How it Works: Instead of just one

Falstaff_Sicksprite, you have three:Falstaff_Neutral,Falstaff_Happy, andFalstaff_Angry.The GBL Win: When the player says the mean thing, the game instantly swaps the sprite to

Falstaff_Angry. The systemic feedback is immediate and clear. My words have a visible impact. I have agency.

2. The “Consequence” Fix (Making Choices Matter)

The Mechanic: A simple, invisible “Attitude” variable for the main character.

How it Works: A helpful choice adds

+1toFalstaff_Attitude. A mean choice adds-1.The GBL Win: At the end of the Adventure, a single line of dialogue changes based on this variable.

If

Attitude > 0: “You were a great help! Thank you, friend.”If

Attitude <= 0: “Well… I’m glad that’s over. Thanks, I guess.”Now the game remembers. My choices have consequences, which is the cornerstone of all great games.

3. The “Real Choice” Fix (Word as Tool)

The Mechanic: A very limited inventory system.

How it Works: In that same scene, Falstaff is sick. He asks for water. But by exploring the room, I’ve “collected” two items in a simple inventory:

[Glass of Water]and[Bottle of Medicine].The GBL Win: Now I have a real choice. Do I give him the water he asked for? Or do I use my knowledge of the situation (he’s sick) to give him the medicine he needs? What happens if I give him the water? Does he thank me, but still look sick? What happens if I give him the medicine? This transforms language from a quiz to a tool for puzzle-solving.

Conclusion: A Fantastic Start, Not a game

Duolingo Adventures is a great step in the right direction. It’s a fantastic, context-rich activity that is light-years better than rote flashcards.

But it’s not a game or to use their own words game-like yet.

The “Falstaff Problem” is the dividing line. By failing to give the player real agency—the power to make meaningful choices and see the world react—it remains a (very pretty, very well-contextualised) quiz.

By adding a few simple layers of agency, consequence, and systemic feedback, Duolingo could stop gamifying learning and start creating a truly revolutionary game that teaches.